Craftivism in a Crisis: Making the Humanities Matter When It’s All Falling Apart

This is a write-up of a talk I gave at CESTA on January 29, 2026, with an epilogue covering the last few weeks. The talk wasn't recorded, and since I wrote this up later, it's less off-the-cuff and probably a bit better than the original. You can find the original slides here (PDF).

It feels like a weird moment to be talking about digital humanities projects. Like many of you, I've got several projects that I'm excited about, and would love to tell you about -- although, if I'm being honest, many of them feel a little stuck, a little stalled out. It's hard to make progress on much of anything.

And it's no wonder: we're in a moment where a future with public support for research and teaching hangs in the balance. We can't assume that the institutions we've worked for, and the systems we've relied on, are going to continue to exist in the same way. Or that we'll be able to continue doing the work we do, in the way that we have.

As we confront this moment of great institutional and societal change, the forces of destruction are the most visible. Budget crises and political forces are colliding, turning important academic programs, centers, and communities into wreckage. But we are not entirely powerless to shape what emerges next. One strength of digital humanities as a community is that -- more than many other areas of the humanities -- we have a track record of talking openly about our values, and these can serve as beacons to guide our actions.

Lisa Spiro's 2011 article "'This is Why We Fight': Defining the Values of Digital Humanities" is a classic of this genre. The last 15 years have complicated some of the values that she laid out in that piece. This is a spoiler for a talk Lisa and I have submitted for DH 2026, but we've revisited those values and reformulated them a little to draw on more recent developments in the field, and what we came up with was:

- Openness

- Collaboration, collegiality & connectedness

- Diversity

- Experimentation & play

- Social engagement & responsibility

No doubt you can already see how these values of digital humanities collide with our current funding landscape. You literally can't get a government grant right now if your application includes words like "diversity". Then again, getting a grant disqualified for diversity reasons presupposes the existence of grant programs to begin with -- and the National Endowment for the Humanities Office of Digital Humanities was eliminated last year.

But maybe the last of these values, "Social engagement and responsibility", which we added in our revision of this list, can point us towards a path forward.

If you've done digital humanities for long enough, you've heard many variations on the theme of "Digital humanities as a neoliberal plot to redirect resources from the humanities into tech". It doesn't come out of nowhere: we've used, and been encouraged to use, rhetoric that offers digital humanities as a backup plan given the jobs crisis in the humanities. Don't get a tenure track job? Do digital humanities and you can get hired by tech companies! Of course, now even CS students at Stanford can't get hired by the tech companies thanks to AI. And the grant opportunities that fed that resentment have largely dried up, unless you can spin it as AI or white Christian nationalism.

Where does that leave us? Let me offer an alternative: digital humanities is a training ground for socially-engaged work in your communities.

Digital humanists aren't the only people looking to help in this moment, but we're better-prepared than colleagues who have gone through traditional humanities training routes. The ideal product of the traditional model of humanities graduate training is a scholar who goes off to the libraries and archives and reads a lot of things and and produces something that is recognizably ✨brilliant✨. And these ✨brilliant✨ scholars are put in positions where they are challenged on their ✨brilliance✨, and the successful ones learn to win these fights in ways that establish and reaffirm their place in the disciplinary intellectual hierarchy. This is why we have to teach grad students in digital humanities classes -- explicitly -- that our field operates under a different set of cultural norms, and the kind of lone-scholar ✨brilliance✨ ready to assertively defend its ranking in the marketplace of ideas will get you written off as someone who's hard to collaborate with. And collaboration truly is the heart of how digital humanities works.

It's how activism works, too. The size, scope, and impact of what you can do as one solitary person is extremely limited. Even if you focus your own activity on a solitary piece of work -- like 3D printing whistles -- odds are you'll want to connect that piece into a larger network of activity, like making whistle kits that pair those whistles with pedagogical materials about your rights, or distributing those kits out to the community. And when your experience as a ✨brilliant✨ scholar is that you can walk into a room, do your thing, and have people fall all over you with praise, you're going to face a rude awakening getting involved in activist circles. If you catch on quickly enough and learn fast, maybe you'll be able to pivot before you alienate everyone you could potentially collaborate with. But it's an ongoing learning process that requires undoing many of the skills you learned to be a successful traditional academic. What happens when you propose something that you know is the right course of action and the group shuts you down? Do you start a schism? Go find a new group of activists to work with? Maybe-- but realistically, how many times can you pull that move? Grad students and staff who have worked on digital projects with a faculty PI learn how to handle this kind of situation, when the project is a good and important one, but the leader is immovably committed to specific features or tasks that you know will backfire, or divert resources from more valuable work. And so you do it, and you deal with the consequences, and you try not to let yourself get bogged down in the feeling of "I told you so" when the consequences arrive, because that's not helping anyone. And you carry on. That's how DH goes, and that's how activism goes.

When I was putting together this talk, the piece that immediately came to mind was Hannah Alpert-Abrams's 2020 post, "What the Humanities Do in a Crisis", which they wrote shortly after a widely circulated think piece in the New Yorker. Let me share an excerpt with you:

Consider this article that the New Yorker just published: what do the humanities do in a crisis?. Here’s how the article describes universities: a cloistered garden. And here’s how the article describes the work of humanists: a life of contemplation. As if humanists are paid to sit alone in the sun, reading Aristotle and thinking about the meaning of life. It’s no wonder I don’t relate to articles like this. Because I work with hundreds of universities, and thousands of humanists, across the country. None of the universities I work with are cloistered gardens. And none of the humanists I work with are paid to live a life of contemplation. Universities as I know them are places of work, not god. And the humanities are sites of action. What can the humanities do in a crisis? So much more than this.

And Hannah goes on to describe some of the things people were doing in 2020. Helping colleagues with strategies for online teaching. Kim Gallon, talking about racial disparities in outcomes for Covid patients. Paula Krebs and the MLA, creating an emergency fund for underemployed scholars affected by the pandemic. And -- in a project I had honestly forgotten about -- Hannah mentions something I was doing, every day remixing a Baby-Sitters Club or Baby-Sitters Little Sister book cover into a "public health message from the Data-Sitters Club" that humorously captured how things were in that moment.

During the pandemic, a group of digital humanists including Hannah Alpert-Abrams, Liz Grumbach, and others, came the Visionary Futures Collective. We ran surveys and visualized the results, gathering and sharing information about how universities were handling remote vs. in-person work, how people felt supported -- or abandoned -- by their institution through this crisis. We collaborated with Claire Chenette, who was shut out of her primary job as an oboist with the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra during the lockdown, and instead used her art skills to paint the images for the Academic Tarot Deck. There were weekly tarot readings, and for those of us lucky to have a copy of this deck, it still serves its purpose in giving us a way to connect and reflect.

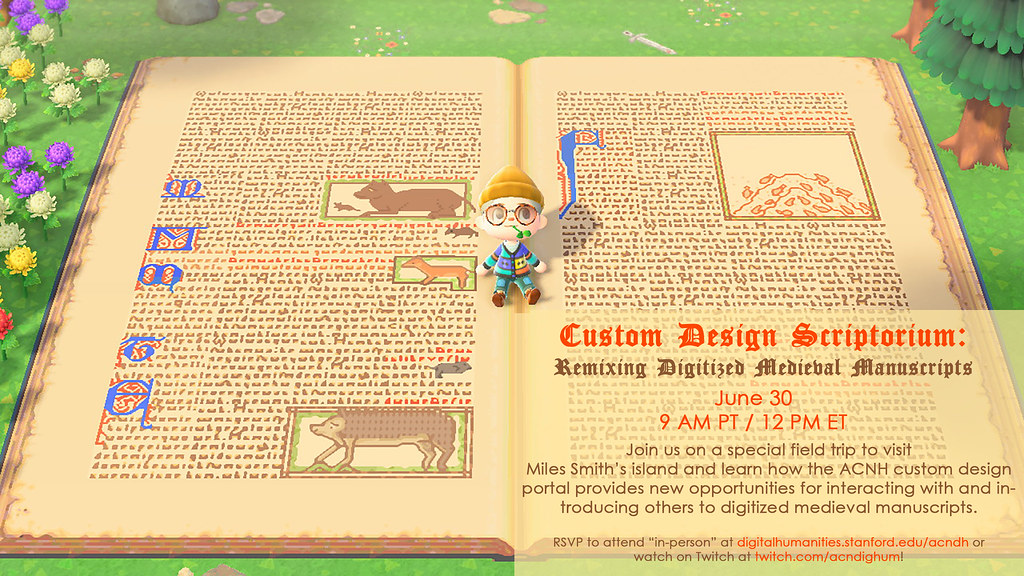

We tried other spaces and approaches, too. You might recall that Animal Crossing: New Horizons came out at almost exactly the same time as the lockdowns, and many people -- myself included -- logged hundreds of hours designing a little community for their virtual self and several talking animal neighbors, while paying off a mortgage to a usurious raccoon and engaging in daily virtual chores and yardwork. But one of the other significant things you could do in that game was visit other people's islands, co-existing in virtual space together in a way that felt more real, more authentic, than just being on Zoom. So Liz Grumbach and I started an academic talk series, "Animal Crossing: New Digital Humanities", where we set up a "DH space" on my island and invited people to come and give a talk. We opened up a small number of "in-person" attendee slots for people to "fly in" their avatar and sit in the audience, and streamed it publicly on Twitch. The talks covered many different topics, from Black digital feminism to handwritten text recognition for Ottoman Turkish to data management horror stories. There was often some festive component afterwards where we could feel like we were actually together -- a crafting party, a costume contest. A talk by Miles Smith, "Custom Design Scriptorium: Remixing Digitized Medieval Manuscripts", involved a "field trip" to their island, where they had used every custom design slot permitted by the game to recreate in gorgeous detail some of their favorite manuscripts, and the rest of the island was crafted beautifully into evocative medieval spaces.

As the pandemic dragged on and travel and large gatherings continued to be logistically challenging, we kept using Animal Crossing as a way to gather together. I remade my virtual home into a lobby, reception area, and banquet hall for virtual DH 2022 "in Tokyo", and took over the whole island to tell the story of the Saving Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Online project, streamed bilingually as one of the pre-conference events.

I had virtual coffee ready on my island for colleagues who were logging onto DH 2022 with me late into the night or early in the morning. You can also see in the background there the ofrenda memorials to DH friends we lost during the pandemic years, Stéfan Sinclair (of Voyant Tools, on the left) and Rebecca Munson (the inspiration behind my purple hair). Part of the whole conference experience is meeting friends in the coffee break room and musing about dubious catering, so I tried to offer that experience virtually. During the ACH conferences, I'd arrange for people to come by, offer them virtual conference swag I'd designed, and the chance to wander around spaces I cobbled together out of digital odds and ends to recreate a world that couldn't exist in that moment.

It was a pressing question in the pandemic in particular: how do you connect with your community when you can't meet in person? I'm proud of the work that the US-based professional association for digital humanities, ACH, did and continues to do with its conference. It sounds cheesy if I try to describe it, but honestly, the 90's JRPG-esque platform that ACH has been using for things like poster sessions and meet-ups, where you walk around in a little virtual space and audio/video engages when you're near other people, is a lot of fun. The ACH conference is primarily virtual for the foreseeable future, but nonetheless we've used it as a space to bring people together around craft work -- but I'll get to that in a moment.

The what's and why's of professional organizations have long been treated as a given: they exist to run conferences and journals and various committees and boards and working groups so scholars can check off "professional service" in their annual reviews. ACH is in an unusual position as a small organization that serves --and is led by -- an interdisciplinary community in a wide range of professional roles. When I got roped into running for VP/president elect, I was told there was just one person running and they needed another nominee. Sometimes I feel like maybe I caused the pandemic by taking this up as my platform -- sorry, everyone -- but my thing was having ACH organize more virtual events. I was a west coast person who was envious and, to be honest, a little resentful about how the East Coast megalopolis crowd could organize events and have people just... hop on a train or in their car and show up for them. Sure, it could be a long drive for people, but out west we have a different understanding of space and distance than folks in those tiny states all smushed together and yet somehow with very distinct cultural identities. I live in the same metro area as my workplace but it still takes two hours to get from home to work. The leadership of ACH had tended to be from this East Coast crew, and I wanted more virtual events so those of us out west could participate. And... again, apologies ... I got what I wanted.

But I got something more than that. Because it turned out that the "other person" running for office was my friend and fellow Data-Sitter Roopika Risam. And we got to talking and she suggested we run together. I thought she was joking, but then thought, what if she isn't? That's a great idea! It's more job than one person can do well, and we bring complementary perspectives to the table.

ACH was willing to go for it, so we both "won", and in the years since, the joint-leadership model has continued and the organization has thrived. ACH has also been on the forefront of weaving this thread of socially-engaged DH into the work that it does, making social relevance one of the evaluation criteria for its conferences.

The emergence of socially-engaged DH predates the pandemic, though not by much. During the transition to the first Trump administration in late 2016, there was a library-based data rescue effort to archive climate change data from federal websites. The outcomes and lessons from that project are a story for another day, but during that administration, there were two projects that became emblems of this kind of work. Led by a team including Roopika Risam and Alex Gil, Torn Apart / Separados documented the policy of family separation at the border, as well as the location and funding for ICE facilities. Needless to say, it is more relevant than ever. Another project led by Alex Gil and others, Nimble Tents, used rapid-response mapathon events where participants contributed to open-source maps used in disaster relief in the wake of Hurricane Maria.

I wasn't involved with either of those efforts, though I was aware of them at the time. I had good excuses, or so I told myself. American studies, politics, immigration activism, it wasn't my lane as someone with a background in Slavic linguistics and a half-library, half-non-English-literature job. And don't get me started on maps. I still believe that even a well-rounded, senior digital humanitist should be able to pick one kind of technology and just write it off as something they don't do. For me that's maps. I hate maps. I hate looking at maps, I hate using maps, I hate making maps. I love that there are people who love maps, and even more people who can just deal with maps like it's no big deal, but I am not those people. Maps are emphatically not for me.

But I ran out of excuses on February 24, 2022 with Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. I was on campus that day, about to commute home when the news broke. The whole ride home, I doomscrolled on my phone. Campus had been gradually reopening, I was working on reopening my Textile Makerspace, and the next time I was there, I used the Cricut to make a "no war" sign for my office window. I stitched up a scarf in the colors of the Ukrainian flag to wear. I took yards and yards blue and yellow fabric and sewed it into a giant Ukrainian flag for one of my grad students in the campus Ukrainian Students Association for one of their rallies, using the tools and supplies on hand to do something.

But then there was a tweet from Anna Kijas, proposing a data rescue event to web archive Ukrainian cultural heritage websites, at an upcoming conference. And Sebastian Majstorovich, in Austria, replied with some possible open source tools to use. This all sounded great, but in those first days, it wasn't clear if we'd be too late if we waited a week. So we started talking and we started building this project we called SUCHO, or Saving Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Online. We secured a small emergency grant from ACH, and then another from its European counterpart, to pay for the first servers to store the web archives we'd started generating. We put out a call for volunteers, and got 400 responses in the first day; the group ultimately grew to over 1,300 people.

One of the lessons I learned from SUCHO is that people want to help. People will donate to causes, and that's vitally important, but people also want to do something. Doing something is the antidote to doomscrolling.

When given a helpful task to do, people get creative. It didn't take long before we had volunteers digging out old laptops and desktops from under their desks, hooking them up to the internet, and setting them up to crawl Ukrainian cultural heritage websites. We even had someone figure out how to run it on a Raspberry Pi! As one volunteer described it, when you're doing web archiving it's like sticking a straw into a body of water and you don't know if it's going to be a can of Coke or the ocean. You just pick a site and try to crawl it until it finishes, and some of those sites turned out to be quite large indeed. We heard from volunteers in our Slack who were deleting all the video games from their personal computers to make space for Ukrainian museum content. If that's not a sign of dedication, I don't know what is.

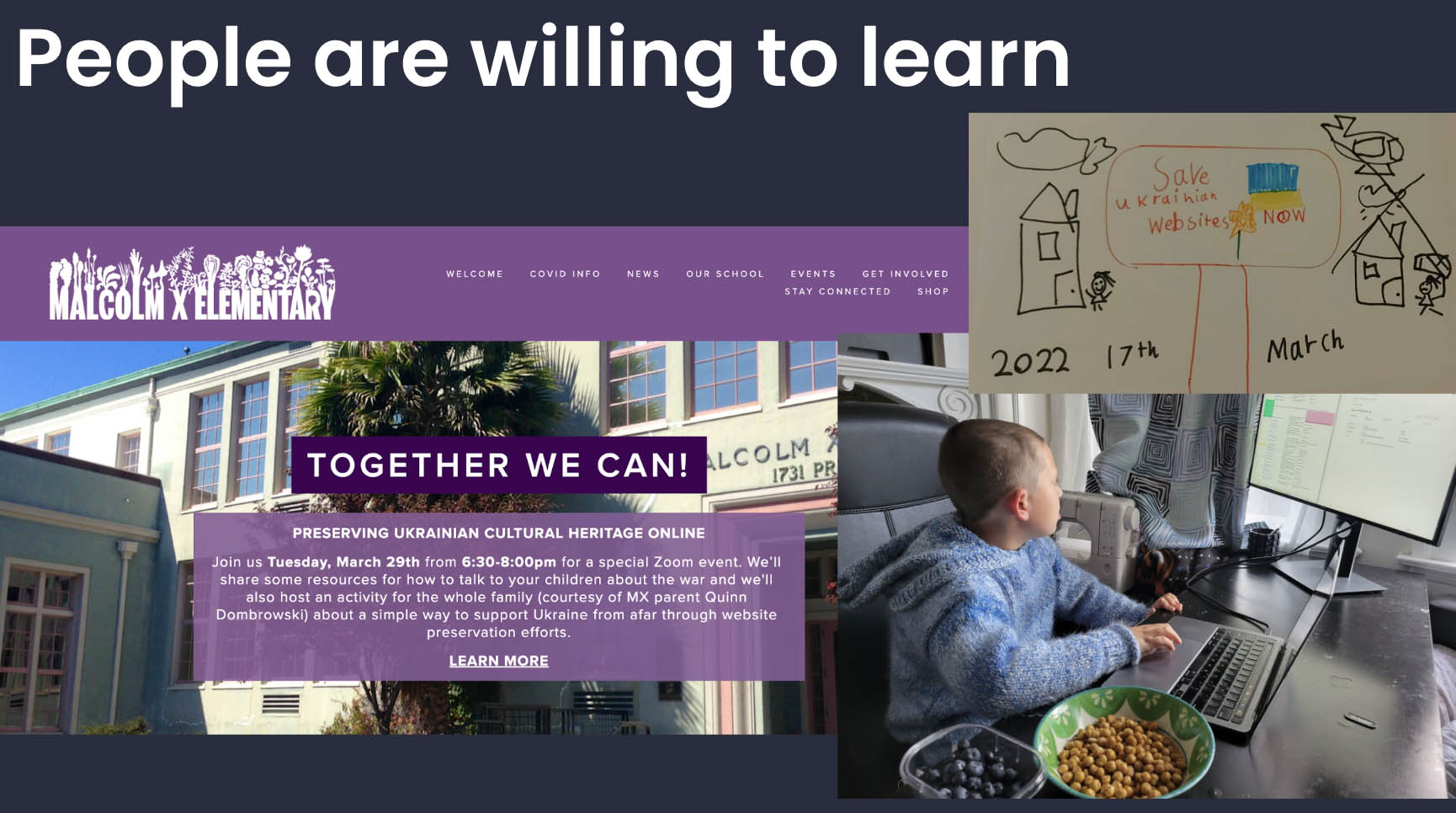

People are willing to learn. I had never really done web archiving before, other than sending some things to the Wayback Machine. It wasn't as bad as mapping, but web archiving was an area of DH technology that I was perfectly happy to leave in others' hands -- at least, until the day when I found myself a core organizer of a Ukrainian cultural heritage web archiving project. When a power outage from everyone's favorite power company PG&E took down the Internet Archive and its web archiving tools for several hours, this hardened our resolve to take a distributed approach to web archiving because it felt like every minute counted. We decided to use the open-source Webrecorder suite of tools for the project to get high-fidelity web archives. The most effective automated tool available at that time, though, required installing Docker and executing the program through the command line. So I worked through the documentation -- excellent stuff, as tech documentation goes, but not something you'd want to hand to someone who doesn't do this sort of thing for a living -- and wrote my own as I learned. Then we started running "getting started" sessions on Zoom, teaching people who had never opened a command line how to do an automated crawl. People started off a little intimidated, but working in digital humanities has taught me both how to learn, and how to teach things that feel scary. So we got through it together, one session at a time.

As luck would have it, Webrecorder had recently gotten a grant for building a user-friendly web interface for their automated crawling tool, Browsertrix Cloud. They had a prototype under development, and SUCHO was right there stress-testing it from the beginning. Not having that barrier to entry meant we could invite more people in. When one volunteer posted a picture he'd drawn with his child after they archived a website together, it occurred to me, "I, too, have children!" And that's how we ended up running, to our knowledge, the first ever web archiving event for elementary school students. The school wasn't back to running in-person events, so we did it on Zoom: curated a list of colorful, kid-oriented websites, showed the kids how to use Browsertrix Cloud, talked a little about the war, and got to watch the wonder on their faces as they saw the preview snapshots of the web archive flash across their screens.

It's easier with children than adults. The fact is, trying new things takes muscles that you can work on developing. Kids are already learning things all the time, so it's no big deal. But adults come with baggage. Maybe it's a lifetime of being told -- or telling themselves -- that they're bad at something. Or a professional identity built around doing this kind of work but not that kind of work; it can't be easy trying to carve out and defend a space for the traditional humanities especially here at Stanford, embedded in Silicon Valley. I started the Textile Makerspace when I was given a departmental computer lab when I started my current job. I asked, "Does anyone use the computer lab? Does anyone want the computer lab?" And what I heard back was, "It's your problem now!" So I got rid of the computers, bought a few sewing machines out-of-pocket, printed out a sign that said Textile Makerspace and taped it to the door... and people believed me. Then they started funding it.

The gambit was this: if my job was to promote and support digital humanities in the department, but the "computational" angle was intimidating, why not lower the psychological barrier to entry? I have all kinds of feelings about this, and can go on at great length about the problematic consequences of "craft" being female-coded, but it does have advantages. Among them, yarn and fabric are less scary than "technology". (In fact they are technology, in the Ursula K LeGuin meaning of the word, but there's a reason she framed that as a "rant".) My hope was that if I could use fabric and yarn to help humanities students develop their muscles for trying new things, that might make it easier to make the leap of trying digital humanities.

But then what started out as a means to an end became something more.

Like SUCHO, #DHmakes started on Twitter. A couple years ago, a few friends and I dug through our Twitter account exports to try to reconstruct its origins, and we traced it to this post by Bethany Nowviskie on the morning of January 9, 2022 about an embroidery sampler she had been working on.

By the next day, we had decided to make it a thing, with a call for more textile-making along with the hashtag #DHmakes.

The DH community delivered-- even going beyond the scope of textiles to include baking, letterpress, and other crafts. The momentum continued past January and was going strong in February... when this story catches up and intersects with SUCHO. One of the last Twitter posts in this early #DHmakes wave was this, which remains sadly relevant four years later. (The transliterated Ukrainian reads 'Putin is a dickhead'.)

Time passed. Elon Musk bought Twitter. Some of us left right away, initially for Mastodon, but Bluesky came onto the scene as a more familiar environment, less entangled in all the complications of politics and policies that happen when your network is actually 500 fiefdoms in a trench coat. For a while, it was invite-only; I got my invite code from someone in the digital preservation community, and invited some friends, and soon Brandon Walsh and I were running a DH Bluesky code bank, where people could donate codes or request them to help the formerly-robust network of DH Twitter migrate to a platform that was not so vocally at odds with our values. (Not to say that Bluesky hasn't made some epically terrible moderation calls, or to deny that the behavior of its execs can at times be somewhere between eyebrow-raising and abhorrent, but it is not actively welcoming towards Nazis nor prioritizing features for digitally undressing people in photos.)

Not everyone from DH Twitter ended up on Bluesky-- and even though I don't use Facebook anymore, I'll sometimes check Instagram or end up accidentally routed to Facebook and be reminded of people I miss because I don't see them online. But enough of the Anglosphere DH world ended up on Bluesky that it feels like some of those conversations were able to continue, despite the disruptive forces that tore up our network. In short, community finds a way.

We handled those years with our own hacks and interventions. For ACH 2023, a group of us manually curated a gallery of #DHMakes posts across different networks, so people could have a holistic picture of the disjointed conversation, regardless of what networks they were on. #DHmakes took on other forms as well: for DH 2023, I filled my suitcase with an assortment of yarn and plastic mesh and wool roving, and went around asking people for their favorite slide from their talk, and found some way to recreate it as a textile, as a custom, tangible souvenir from the conference.

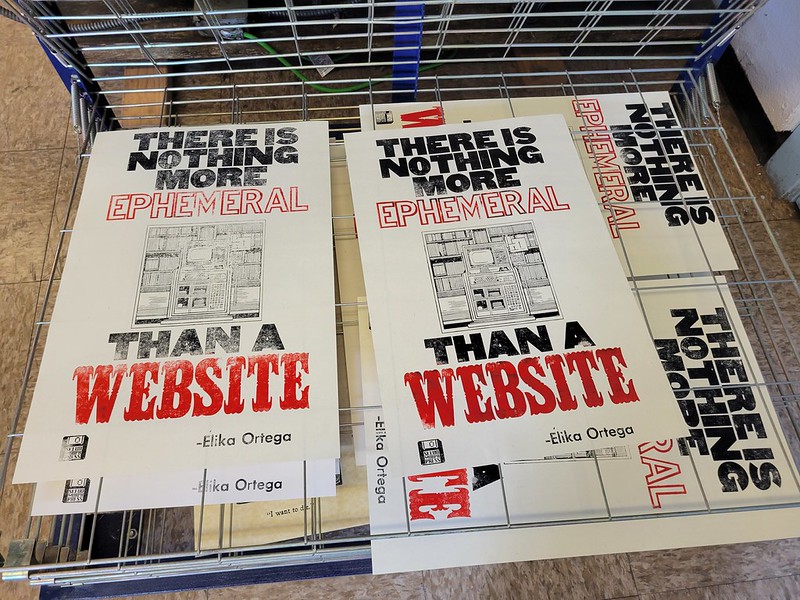

The tensions between the digital and the physical in the work that we do took on other shapes. When I was visiting my library school alma mater UIUC to give their 2024 Windsor Lecture, I got to visit my old friend Ryan Cordell at his Skeumorph Press. Together, we made a print that now adorns my walls and many others', as it took off on Bluesky and became a fundraiser for the press. "There is nothing more ephemeral than a website." Élika tells the story of that quote as she remembers it here; in my recollection, it was Hannah Alpert-Abrams telling me about a conversation they had with Élika where they were lamenting that they no longer built websites and did digital humanities stuff, but had been spending a lot of time embroidering. And Élika pointed out to them that those embroideries would be a lot more durable than any website they could be making instead, because... well. We know too well the problems with websites.

Even with their ephemerality, we live on websites. It's where we find our friends and share the marvelous things we make -- or try and fail at making. #DHmakes has thrived on Bluesky, bridging the digital humanists whose craft and making is deeply engrained in their academic work, digital humanists who craft on the side and are excited to share what they've made, and people who have never heard of digital humanities, but are doing compelling craft work that resonates with the spirit of #DHmakes.

I love preparing a talk like this because I get to share some of the delightful things that have been posted with that hashtag, even just in the last few weeks.

Sara Arribas Colmenar, who was here for the Flamenco workshop in December, makes these incredible physicalizations of networks of dancers using nails and string. She's recently finished one big piece and is starting on new ones. Pam Lach and I have insomnia in common, and even though she'd never really done craft work before, she liked the idea I started of tracking my bad sleep in the form of embroidery. I gave up on it myself, but she's done two full years of it and made these beautiful data visualizations.

It's hard to capture in a single still image, but Emily F. Brooks made this marvelous poster that reads "book history", "design", and "digital humanities" -- and which is more prominent depends on what kid of light you shine on it. Abby Mullen knit a blanket with her reading for 2025, non-fiction in dark gray and fiction in light gray. There was so much that December had to go vertically, which made the whole thing look like a book with a spine!

Amanda Visconti is wrapping up a residency at Penland School of Craft, and posting all their wonderful letterpress experiments. Meg Smith shared a print that Amanda made for her with a quip that Meg made at the ACH conference last year: "Infrastructure is something we owe to one another." I think about that a lot, still. Andy Famiglietti has been diving deep into 3D printing, including whistles for his community.

I was talking with Amanda recently and it occurred to us that there hadn't been enough sharing failure in #DHmakes, even though failure is very much a theme in the digital humanities work I do. And particularly in a time when it's trivially easy to throw some words into a text box and have a visually sleek, polished "art" extrude out the other side, we thought it was important to celebrate the humanity of the process, even when the outcome isn't exactly what you'd want to call good. And out of that, #DHtries was born.

There's a lot of people making things right now, in more media and using different tools than I would have ever imagined. Ice luminaries on a frozen lake. Stained glass. Markers on mailing labels.

Street art. Embroidery. Crochet.

Hats. Quilts. Patches. Embroidery.

And I want to give the final word to Minneapolis, with a video from someone on the ground, talking about what he's doing to help. It really resonates with me, and what I've gotten out of more than 20 years of doing digital humanities. So I'll turn it over to Art Price:

I'm Art Price and I am putting free prints on the shirts and other fabric that anyone brings us to print on. I decided to start doing this because I have this cooperative screen printing studio space that I run and I didn't have a lot of shirts but I have a lot of equipment and ink and I was very, very angry. The response from the community has been absolutely incredible. I've had a group chat of volunteers, more than 50 people deep. I've been able to arrange for people who don't feel safe coming to get a shirt, to have a shirt taken to them. I've had folks donating time, money, food, everything. I've had people coming in bringing whistles. We've had people who bring by red cards to distribute to people as well. We've got cookies that had sprayed on them "fuck ICE", just on the cookies. I have had some people show up in ways that I have never experienced before in my life. I have felt more in community in the last week than I have in the last five years. If someone wants to get plugged in and doesn't know where they fit, they should find a place where people are already doing something and talk to the people who are doing that. Just because you haven't done anything before doesn't mean you can't do anything. As Jake the Dog once said, "Being really bad at something is the first step to being kinda good at something." And if you show up, they will put you to work. There's work to be done and we will show up.

Epilogue

In the two weeks since I gave this talk, I've added a 3D printer to my at-home crafting tool arsenal. The base plate is always hot and the filament flows freely, as close to 24/7 as I can manage, printing whistles. (At least mostly whistles. Once a day, in between sets of whistles, I print one random small whimsical thing to drop off in my neighborhood "take an art, leave an art" box.) Inspired by Bree Bridges (who's coauthored delightful dystopian sci-fi featuring mercenary librarians), I'm also collecting the misprints from my whistle-printing and others'. I have a vision of turning these stringy messes into some kind of embroidery using a couching stitch.

Craftivism spent a day or two at the center of the Discourse on Bluesky, with people like activist Kelly Hayes weighing in, and Alyssa Long had a roundup of links to recent articles, including a Guardian article on "rage knitting", a Salon article drawing parallels and contrasts to the earlier pussy hats movement, and an interview with the designer of the popular red hat pattern. There are other good recent threads by Parkrose Permaculture and Cerie Priest.

There was a question after the talk about how to get involved with local activism, and I honestly said I didn't know. These groups operate extremely locally -- so much so that, as someone who lives a 2-hour drive away from their job -- I don't have any handle at all on the scene around work. But Art Price's advice from Minneapolis is good: look for places where people are doing things, and go talk to them. If you're used to throwing words at a search engine or a LLM and running with the AI summary answer, this is the opposite of that. You need to go out, in person, into the world around you and talk to people, coming from a place of curiosity and humility and desire to learn. You may still get told off from time to time. But being in community with your neighbors -- stuffing whistle kits, or holding signs on the overpass, or wrangling spreadsheets, or knitting hats together -- is meaningful and powerful, and different than our sprawling virtual digital networks. But we're there, too. Come find us, then put down your screens and find your neighbors.